Richard Leadbetter isn’t usually the type to make headlines outside his own niche. His home turf is frame-rate graphs, pixel counts, and explaining to the rest of us why one version of a game runs two percent smoother than another.

But on a humid Thursday in August, the founder of Digital Foundry lobbed a different kind of video into the internet. No benchmarks. No resolution charts. Just Leadbetter, calmly telling the audience that after nearly a decade with half his company owned by IGN and its parent Ziff Davis, he had bought it all back.

It wasn’t a flashy production. No corporate anthem swelling in the background. Just a matter-of-fact announcement that a stake once sold to Eurogamer’s Gamer Network in 2015 (later inherited by Ziff Davis) was now out of corporate hands for the first time in years.

“We answer to nobody but you, the audience,” he said. The line wasn’t shouted, but it landed like a declaration.

Within hours, screenshots of the statement were ricocheting across Reddit threads, Discord servers, and YouTube comment sections. A niche tech outlet had suddenly become a symbol of something bigger: the rare act of a publication buying back its own voice.

And in an industry where most of the mastheads you know are owned by just a handful of media conglomerates, that’s not just a nice story. It’s a statistical anomaly.

The invisible owners

If you lined up the logos, you’d think gaming media was a bustling city of rival neighborhoods. IGN on one corner. Eurogamer across the street. GameSpot down the block. Polygon and Kotaku, a few avenues over, lobbing opinion pieces like flyers.

But walk a few blocks behind the storefronts and you’ll notice something strange: A lot of these streets lead to the same few buildings.

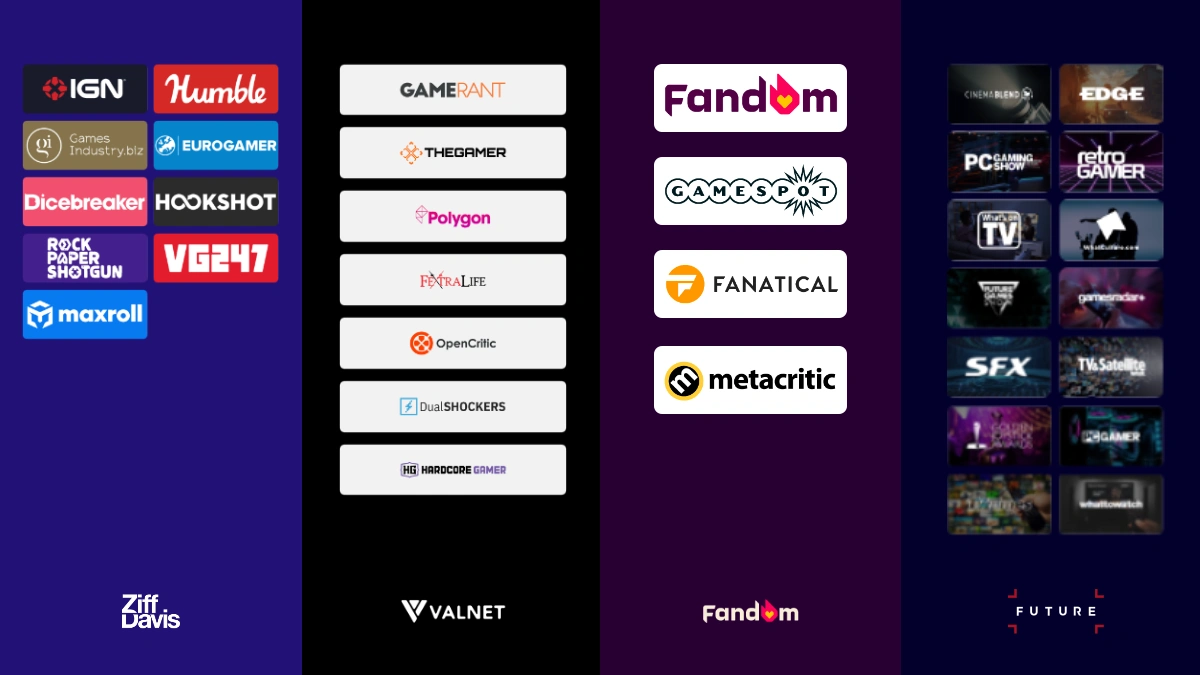

Take IGN, the name that’s practically synonymous with game reviews. It doesn’t just stand alone. It’s the flagship of Ziff Davis, a publicly traded digital media conglomerate with board members and quarterly earnings calls.

In 2024, IGN quietly expanded its grip, buying Gamer Network, the UK company that ran Eurogamer, GamesIndustry.biz, VG247, and Rock Paper Shotgun. Overnight, those sites went from being friendly competitors to siblings under the same corporate roof.

Then there’s Fandom, a brand that started as a fan wiki platform before ballooning into a media empire with the backing of private equity firm TPG Inc. In 2022, Fandom shelled out for GameSpot, Metacritic, GameFAQs, and Giant Bomb—properties it scooped up from Red Ventures like they were on a clearance rack.

Future PLC, a UK publisher with a taste for acquisitions, owns GamesRadar, PC Gamer, and Edge plus dozens of non-gaming titles, all feeding into a sprawling content machine that knows how to stretch one story across multiple sites for maximum clicks.

The Kotaku carousel

And then there’s Kotaku. It’s been passed around like an unwanted controller: launched under Gawker, sold to Univision in 2016, spun into G/O Media in 2019 (where private equity firm Great Hill Partners pulled the strings), gutted by staff departures, and finally sold off in 2025 to Keleops, a French digital publisher that most of Kotaku’s readers had never even heard of.

With this many changing hands, one thing is clear: Kotaku is not the same publication it was when it launched over 20 years ago.

Valnet Inc., another quiet powerhouse, scooped up Polygon from Vox Media in 2025, adding it to a stable that includes Game Rant and Screen Rant. Polygon, once the crown jewel of “new games media,” became another cog in Valnet’s content factory.

Even supposed competitors turn out to be siblings. IGN and Eurogamer? Same parent. GameSpot and Giant Bomb? Both Fandom’s property until Giant Bomb bought itself free this spring.

From the outside, the industry looks like a marketplace of ideas. From the inside, it’s a handful of holding companies playing Monopoly with the mastheads.

When ownership collides with journalism

It doesn’t always take a boardroom memo to change coverage. Sometimes the clash between editorial judgment and corporate interest plays out in public and the scars stay visible for years.

The most infamous case still echoes: Jeff Gerstmann’s firing from GameSpot in 2007. Gerstmann, then the site’s editorial director, panned Kane & Lynch: Dead Men with a lukewarm score. At the same time, publisher Eidos had paid for a heavy ad blitz plastered across the site.

Days later, Gerstmann was out. Official statements danced around the reason, but he later confirmed what everyone suspected: ad dollars and editorial honesty had collided, and honesty lost.

The 2020 exodus

Thirteen years later, a new cycle of ownership stirred similar tension. In 2020, Jason Schreier left Kotaku after a decade of scoops and investigations. His reason was blunt: “dissatisfaction with the direction” under G/O Media’s new private equity owners, Great Hill Partners. Several other reporters followed him out the door, citing corporate mandates and the slow erosion of editorial independence.

Even this year, the story repeated with different players. Giant Bomb put content on pause amid reports of “editorial interference” by Fandom, its parent since 2022. Staff described pressure to reshape their work around algorithms and SEO priorities. Instead of bending, the team negotiated an employee buyout and went independent while declaring, pointedly, that they were “not serving an algorithm or executives anymore.”

These aren’t isolated flare-ups. They’re reminders of what happens when journalism lives inside a corporate balance sheet: sooner or later, the numbers start tugging at the words.

The stories you don’t get to see

The headline-grabbing clashes like Gerstmann’s firing, Kotaku’s walkouts, and Giant Bomb’s breakaway are easy to point to. But the subtler story is the one readers never see: The articles that never leave the pitch doc, the drafts that get watered down before they reach the front page.

This is the quieter form of corporate influence, and it’s arguably the more damaging one.

When a parent company’s revenue depends on publishers buying ad packages, there’s an invisible ceiling on how far a negative review can swing. Audiences even have a shorthand for it: the “IGN 7.”

The meme lives on because it captures a real skepticism that no matter how disappointing or buggy a blockbuster is, the score on the biggest sites always seems to hover around a safe seven out of ten. Fair or not, it reflects the nagging question readers have asked for years: when the outlet’s paycheck comes from the same companies it’s reviewing, how low can the score really go?

And the thing is, it doesn’t take a blunt order from the top. Sometimes it’s an editor nudging a writer to “tone down” a harsh phrase. Sometimes it’s a rewrite that tucks a damaging detail deep into the copy. The result is the same: reviews that sound a little softer than players expect, and criticism that feels more like hedging than honesty.

The same dynamics shape news coverage. Outlets whose parents run major conventions or events often hesitate to report aggressively on those same sponsors. A harassment lawsuit, a union drive, a messy leadership change—all risky to cover if the company in question is bankrolling a hall at PAX or Gamescom. What gets described as “editorial discretion” is often just business calculus.

Even watchdog topics such as loot boxes, predatory monetization, studio labor practices sometimes get uneven treatment. When Electronic Arts’ FIFA Ultimate Team controversy broke, smaller blogs and YouTubers pounced.

Larger outlets followed, but cautiously, after the issue reached governments and regulators. For years, critics inside the industry have argued that corporate-owned press tends to wait until it’s “safe” to speak loudly.

When stories disappear

And then there are the stories that vanish entirely. In 2013, CBS (then parent of GameSpot) pulled a CNET review of Dish Network’s Hopper DVR, citing an ongoing lawsuit. It wasn’t even about games, but it revealed how quickly a corporate owner could yank coverage to protect its interests. Staff at the time described the decision as a chilling effect on what they felt free to cover.

That chilling effect is hard to measure, because it looks like absence. You won’t notice the labor story an editor declined to greenlight, or the review that stopped short of saying “broken.” But those silences add up.

Independent outlets, by contrast, don’t have those tripwires. When Spilled covered the Collective Shout controversy, bigger publications seemingly ignored it. Whether it was sponsor fear, legal caution, or simple unwillingness to wade into a messy cultural fight, the result was the same: readers were left with partial coverage. Independence meant we didn’t have to weigh how a boardroom or advertiser would react before hitting publish.

The truth is that ownership doesn’t always dictate what gets written but it absolutely dictates what doesn’t.

The independence wave

Digital Foundry’s buyout could have been a footnote—a niche site with a loyal YouTube following cashing in on its success. But Leadbetter’s phrasing made it clear: this was about more than ownership papers.

He described the deal as “staggering,” admitting it cost “more than my house”. For the first time since 2015, he and his team controlled everything: the brand, the archives, the direction. “All aspects are decided by us,” he said.

That declaration resonated far outside DF’s subscriber base. In May, Giant Bomb’s staff pulled a similar move, buying the site back from Fandom after months of tension over “editorial interference.” The message was nearly identical: better to be small and answer to your community than large and answer to an algorithm.

Video Games Chronicle has charted this course since 2019, staying editorially independent under its parent 1981 Media Ltd. That status is rare enough now to be a selling point; a promise that its scoops and exclusives aren’t routed through corporate filters. However, a partnership established in 2019 that put Gamer Network in charge of advertising and sales puts VGC in a gray area when it comes to gaming journalism.

And then there’s us—Spilled. Unlike Digital Foundry or Giant Bomb, we never had to cut a buyout check or unshackle ourselves from a parent company. And unlike VGC, we manage every aspect ourselves. Independence has been the default here and not a choice made after a crisis, but a principle baked in from the start.

It’s why we can run stories about Roblox potentially allowing and fostering an unsafe environment for children when others won’t, or critique the future of esports without worrying about how it looks to a sponsor. Our calculus isn’t “will this upset the board?” It’s “is this true, and does the audience need to hear it?”

In an era where independence is increasingly treated like a luxury, the truth is simpler: it’s survival. The new wave of outlets, like Digital Foundry, Giant Bomb, VGC, and Spilled, are staking their futures on the idea that audiences value honesty over polish, and candor over corporate diplomacy.

Why ownership matters

Most of us don’t think twice about who owns the byline we click. A review is a review, a news hit is a news hit. But the fingerprints of ownership are always there — sometimes obvious, like a firing that sparks headlines, sometimes invisible, like the story that never gets commissioned.

When Jeff Gerstmann lost his job at GameSpot, it wasn’t just about one review. It was about the tension between ad money and honesty. When Jason Schreier walked out of Kotaku, it wasn’t just a career move. It was a signal that the editorial floor was no longer steering the ship.

When Giant Bomb bought itself free from Fandom, it was proof that even beloved brands can find themselves reduced to line items in a corporate strategy deck.

Ownership shapes what gets said. More importantly, it shapes what doesn’t.

The freedom to say no

That’s why independence matters. It doesn’t guarantee brilliance, but it guarantees the freedom to call a game broken even if the publisher is buying ads, or to cover labor disputes even if the studio is a convention sponsor. It means there’s no middle manager weighing shareholder optics against editorial judgment.

At Spilled, that’s been our baseline from day one. We don’t have to unplug from the corporate network because we were never plugged in. No conglomerate, no equity firm, no overseas parent. Just editors who care about telling the stories that matter whether that’s breaking down esports’ growing pains, questioning industry silence, or covering controversies others won’t touch.

For readers, that independence translates to something simple: trust. You know the words you’re reading aren’t bent around an ad buy or softened to protect a brand relationship. They’re bent only toward the truth as best we can tell it.

So the next time you see a familiar logo at the top of a page, ask yourself who owns it and whether that ownership changes what you’re about to read. In today’s gaming media, odds are it does.

And if you’re looking for the exceptions… well, you’re already here.