Since its launch in 2003, Steam has completely reshaped how we buy, play, and even think about games. Steam grew from a simple software to update Half-Life 2 into the biggest digital storefront in gaming, with a library that spans everything from underground indies to major blockbusters.

While most PC gamers know about Steam, less know about the company that’s behind this major storefront, Valve. With some of genre-defining games like Half-Life, Portal, or Counter-Strike, the most popular PC gaming storefront, and a president that is sometimes referred to as the gaming god, Valve managed to revolutionize gaming, one innovation after the other.

Redefining expectations for PC games

Valve started in 1996 as a side project between two former Microsoft employees, Gabe Newell and Mike Harrington. They weren’t trying to build a platform or even a studio with staying power: They just wanted to make a game. That game was Half-Life.

Getting it published wasn’t easy. Most publishers didn’t know what to make of a first-person shooter with no cutscenes, no levels in the traditional sense, and an unusually ambitious AI system. But in 1998, Half-Life finally came out and became a hallmark in the FPS genre. By 2014, IGN would write that the history of first-person shooters “breaks down pretty cleanly into pre-Half-Life and post-Half-Life eras.”

To develop Half-Life, Valve modified the Quake engine and built its own hybrid version, called GoldSrc. In 1998, Valve bought TF Software, the team behind the Team Fortress mod, and released Team Fortress Classic the following year on GoldSrc. Around the same time, Valve opened the engine up to the community with a software development kit (SDK), encouraging players to mod their games.

That decision paid off. One Half-Life mod in particular, Counter-Strike, quickly exploded in popularity. Valve brought the mod’s creators in-house and turned it into a standalone game.

The early pattern was already in place: build tech, support creators, and absorb what works. Valve would later recruit more modders to launch standalone games like Dota 2, all while continuing to improve its engine, and even delve into the development of its own hardware.

Full Steam ahead

Six months after the release of Half-Life, Valve began working on a sequel using its new in-house engine, Source. Upon its release in 2004, Half-Life 2 won various Game of the Year awards, and is still to this day considered one of the best FPS ever made.

However, playing Half-Life 2 came with a condition. The only way to install Half-Life 2, and to update Valve games was to install the company’s digital storefront: Steam. And the players weren’t too happy about this, with many seeing it as an unnecessary requirement, a frustrating piece of software that complicated what used to be simple.

Over time, Valve opened Steam to third-party games. More developers signed on, and more users followed. In 2025, there are about 132 million monthly active users on Steam, over 200,000 games, with sales reaching an all-time high of $10.8 billion in 2024. Every year, developers put their games on Steam, from large AAA titles to indie gems trying to find their audience.

Throughout the years, Steam added features that became staples in the gaming industry: user reviews, automatic updates, Early Access, regional pricing, and a refund system that actually worked. While these tools weren’t unique to Steam, they were a core part of Valve’s storefront and became standard for the gaming industry.

The International and Valve’s presence in esports

While Steam took off, Valve continued to release new games. Team Fortress 2 and Portal launched in 2007. Left 4 Dead followed in 2008. In 2009, Valve hired IceFrog, the developer of the original Defense of the Ancients mod, to lead work on a standalone sequel.

Dota 2 was released in 2013, and Valve paired it with a major esports tournament: The International. To fund its prize pool, The International relies on a crowdfunded cash prize driven by in-game battle pass sales. It was the first major publisher-backed tournament of its kind, and the prize pools eventually reached tens of millions of dollars.

Making millions without selling new games

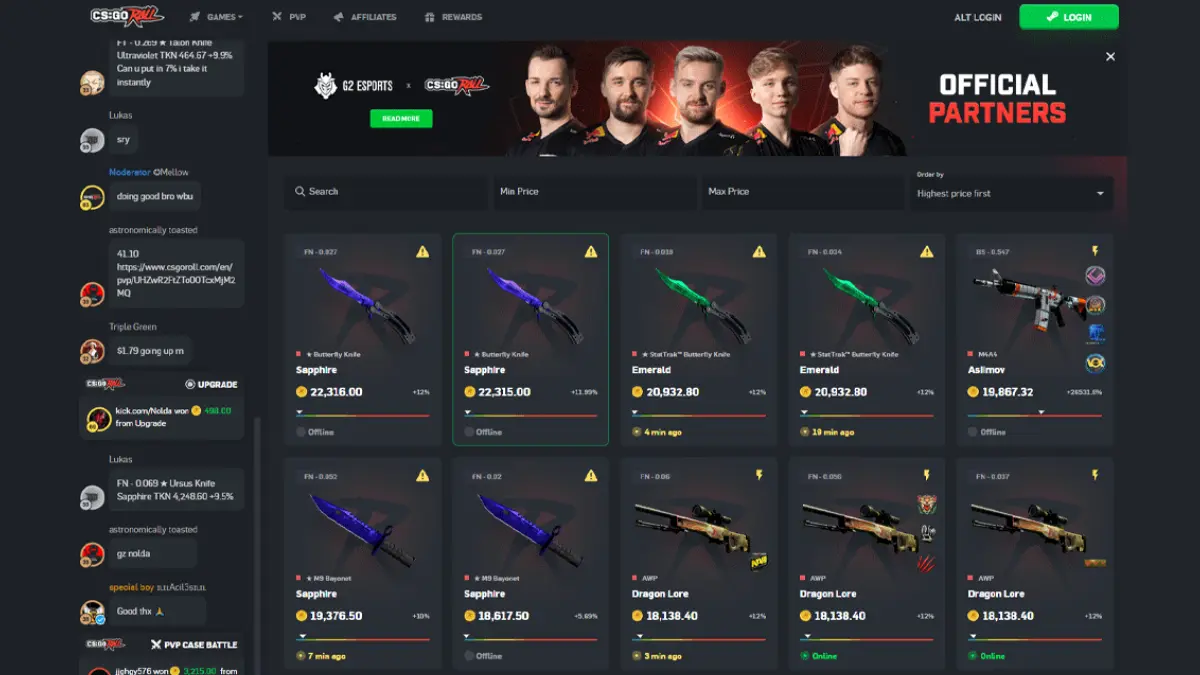

This community-led funding for Dota 2’s major esports tournament isn’t the only way Valve is getting money from its users. In June 2012, Valve hired the economist Yanis Varoufakis to study the online economies of their games, and they found a way to gather millions. Steam features a marketplace for players to trade in-game collectibles, like weapon skins in Counter-Strike, cosmetics in Dota 2, or digital games trading cards.

In Counter-Strike, one of the most popular games on Steam, players can customize their weapons with skins. To get a new appearance for their weapons, players have two options: be lucky enough to earn them through random drops on official servers, or open a weapon case.

That’s where it gets tricky: to open a case, players need to buy a key. Each one costs $2.49, paid directly to Valve. However, opening a case doesn’t guarantee that players will get the skin they’re looking for. Instead, they get a random loot from a selection, creating an entire gambling aspect in the game.

Players who don’t want to gamble can head to Steam’s marketplace, where skins are traded directly between users. But this marketplace also has its hooks. Prices are dictated by supply and demand, with rare skins selling for absurd amounts, some reaching over $400k. The system also loops right back into case openings, as the only way to pull a jackpot-worthy skin is by opening more cases.

Valve is the real winner either way. The company either takes $2.49 for every key, or a 15% cut on every marketplace transaction (5% for Steam and 10% as Counter-Strike 2’s publisher). In 2023, Valve made close to $1 billion solely through Counter-Strike’s skin market. In March 2025 alone, players opened over 32 million cases, netting Valve almost $80 million in a single month.

Valve isn’t as perfect as it seems

This trading system and case openings in Valve games led to critics blaming Valve for promoting gambling among younger players. Valve has faced lawsuits and regulatory pressure in multiple countries over this, but it continues to support the skin economy. It remains one of Steam’s most lucrative features, with Counter-Strike 2 cases bringing in $82 million in March 2025 alone.

There’s no reason Valve would stop taking its cut on Counter-Strike skins. While the company shut down many gambling sites back in 2023, it doesn’t stop the problem at its core. Players are still encouraged to purchase keys in hope to get a rare skin, creating an ever-ending cycle of gambling behavior.

And the reason is quite clear. According to a report by Forbes Australia published in December 2024, Valve had an annual revenue of $5 billion by 2023, with a 40% profit margin. Steam accounted for around 60% of this revenue, double that of 2019. With about 350 employees, this amounts to about $14 million in sales per person, making Valve more profitable per employee than some of the most valuable companies in the world, including Amazon, Google, and Microsoft.

A different kind of company

Unlike other gaming companies, Valve doesn’t have bosses, stakeholders, or anyone pushing the company to pump out new games on a regular basis. Gabe Newell, the president of Valve, owns just over half of the company (about 50.1%), with the rest of the company owned by employees. There is no CEO or board of directors calling the shots day-to-day. Instead, Valve maintains a flat hierarchy. Employees have the freedom to form teams and work on whatever they want.

While this may sound like a dream place for many employees, this flat structure comes with pros and cons. Since it is a system built on self-selection, it lets developers chase good ideas without the pressure of making money or meeting tight deadlines. However, since there are no official leaders to impose a strategic direction, projects can fail if employees are not interested in them.

In 2023, a video from People Make Games based on interviews with current and former Valve employees outlined the downsides of that flat structure. The interviews pointed to a lack of diversity and inconsistent support for projects. Moreover, Valve features a stack ranking, where employee bonuses depend on peer evaluations, encouraging popularity over collaboration.

Since Steam makes most of Valve’s money, the company doesn’t need to regularly publish games to stay profitable. While that may seem counterintuitive to run a business, it lets Valve’s employees focus on projects they care about and develop new ideas to innovate and push products no one outside of Valve could afford to create.

Valve, the wannabe Nintendo

In the 2010s, Valve shifted some of its focus to hardware. Gabe Newell spoke openly about his interest in building hardware and software together, pointing to Nintendo as a model. But making it in the console industry isn’t an easy feat, and it took Valve a few trials and errors to get there.

The Steam Machine, a line of Linux-based gaming PCs, launched in 2015. By June 2016, fewer than half a million had been sold. But that commercial failure didn’t stop Valve from wanting to create hardware.

Valve moved on quickly. The company partnered with HTC on a VR headset, the Vive, which was released in 2016 and helped set early standards for PC-based VR.

In 2019, Valve released the Index, its own VR headset, and announced Half-Life: Alyx, a VR-exclusive entry in its flagship series. The game received strong reviews and drove a spike in Index sales, but the platform remained niche. By the end of the year, only around 150,000 Index headsets had shipped.

Still, since Valve employees can work on any project they’d like, they didn’t stop trying. And in 2022, Valve released the Steam Deck.

The Steam Deck supremacy

The Steam Deck is a handheld gaming PC built to run SteamOS. It combines the portability of a console with the flexibility of a PC. And most importantly, it is backed by a library that already exists, so Steam users don’t need to spend anything extra to play games they already own.

The Steam Deck found a user base quickly. It runs recent AAA games, supports mods and emulators, and fills a niche that the rest of the hardware market largely ignored. In many ways, it reflects Valve’s core strength: embracing what the gaming community needs, more than looking for ways to sell additional games. By 2025, Valve sold over five million Steam Decks.

Why Valve stands out

Valve isn’t a traditional gaming company. It’s not only a developer or a publisher. It’s not a console manufacturer, nor a storefront. It’s all of that, and even a little more.

Valve built tools, games, hardware, and a gaming platform. Instead of focusing on making its own games popular, it embraced diversity and included third-party games of all sizes and budgets. It didn’t refrain users from creating mods, it pushed them to do so, and even hired the best ones. Steam doesn’t require any kind of subscription, nor does it feature ads—only sales, constant backend updates, and a seemingly endless choice of games.

In an overly competitive industry, Valve stands out as a company that aims to deliver quality products, even if it means delaying releases or scrapping projects entirely. And while Valve faced some failures, like with Left 4 Dead 3 and Valve Index, it still kept on doing what it wanted. In the end, Valve made a lasting impact on the entire industry with genre-defining games, the most popular PC games storefront, and one of the most popular handheld consoles of recent years.

Gabe Newell, the PC Gaming God

On top of being a customer-centric company that delivered great software and hardware, Valve has one key asset: its president, Gabe Newell.

Over the years, Gabe Newell’s low public profile despite the popularity of Valve only boosted his reputation in the gaming community. Despite having a net worth of about $9 billion and running one of the most beloved gaming companies in the world, Newell has been known to stay relatively down to earth.

He directly responds to emails from fans, and in 2022, he personally hand-delivered Steam Decks to early customers around the Seattle area, signing devices and taking pictures along the way.

Although Gabe Newell has often kept out of the spotlight, he gradually became the public face of Valve, and, for some fans, something of a cult figure. Online communities began portraying him as the god of gaming, dedicating him an entire subreddit. As president of Valve, Newell consistently prioritized players’ needs, earning a reputation for putting the gaming experience ahead of financial profit–not that it stopped him from amassing billions.

What’s next for Valve

While Valve may not be the most well-known company in gaming, its impact on the entire industry remains undisputed. From Half-Life and Portal to Steam and the Deck, Valve has been changing the way players purchase, interact, and play games.

Valve doesn’t chase trends. It doesn’t release games to meet a fiscal quarter. And it doesn’t explain itself. This is part of what makes it frustrating to follow and difficult to critique. The company launched genre-defining games, built a device letting anyone play their PC games without a computer, and created a platform that shaped how games are bought and sold. It also profits from systems, like weapon skins and case openings, that continue to raise ethical questions.

So, what’s next for Valve? Over the past decades, Valve has been innovating where people expected it less, and, often, to the public’s disapproval. Steam wasn’t popular at first. Neither was Valve’s hardware. But both Steam and the Deck are among the most popular platforms these days. So who knows what Valve could be up to next—except, probably, Half-Life 3.