Fontworks, a major Japanese font provider widely used across the country’s game industry has raised licensing fees by over 5400% following acquisition by US company Monotype. This change in ownership has seen the price of font licensing rise from $380 to $20,800 per year.

The new licensing structure of the company’s licensing service “LETS” also caps coverage at 25,000 end users per license. Games with larger player bases would need to purchase multiple licenses or negotiate higher-tier agreements, and a game with 100,000 active users could face annual font costs exceeding $80,000 under the new model.

Unlike the English language, Japanese has a huge number of different characters that must be represented in writing, and finding high quality fonts that include Kanji, Hiragana, Katakana, punctuation, and special symbols is difficult. LETS used to provide this service to customers from game studios to single professionals at an affordable price.

This complexity makes Japanese fonts expensive to produce and limits the number of professional foundries capable of creating them. The concentrated market leaves developers vulnerable when a major provider changes terms.

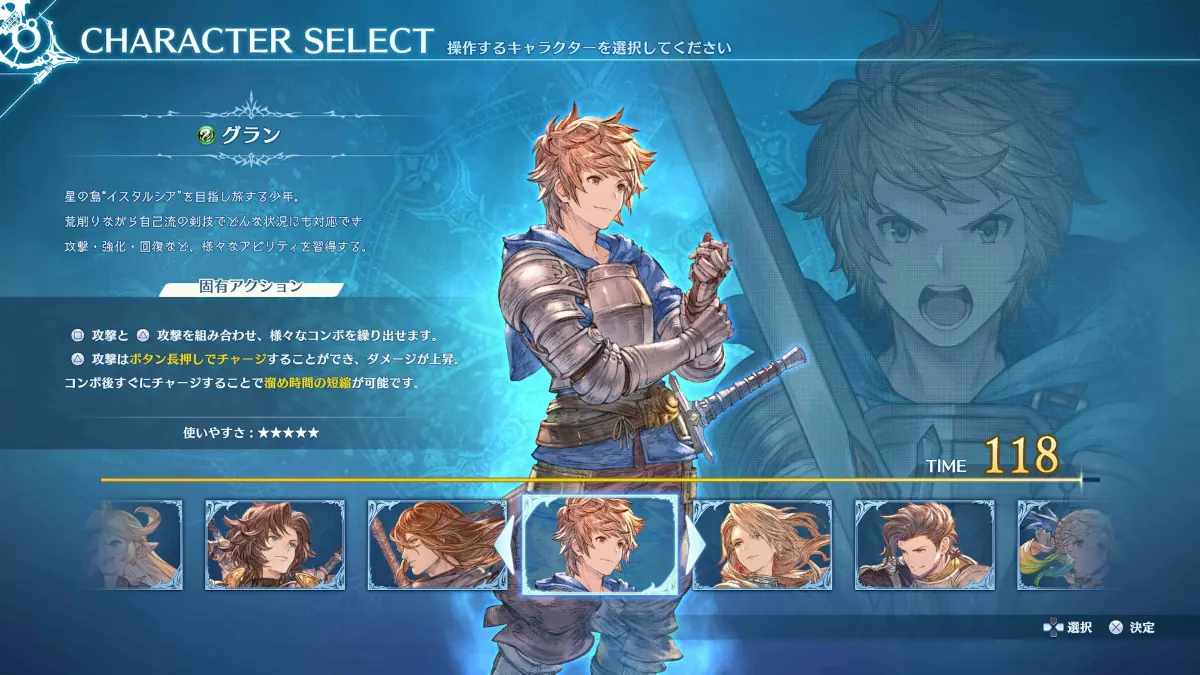

Live-service games could be hit the hardest by this change. These titles often boast player bases in the 100,000’s to millions, so paying recurring annual fees that scale with user count incurs huge operational costs. In addition, many single player games such as the Persona series, Granblue Fantasy, Final Fantasy and more have made use of the service extensively.

Switching fonts post-lanuch would not be cheap either. Requiring new UI layouts, re-testing all screens and dialogue, and deploying patches across all platforms simultaneously demands a lot of extra work from developers. For games with elaborate interfaces and extensive text content, the work can take months and risk introducing visual bugs.

Japanese copyright law treats font design differently than many Western jurisdictions. While font file data itself carries copyright protection, the visual appearance of individual glyphs generally doesn’t. This legal framework allows “lookalike” fonts that replicate a typeface’s appearance without copying the original digital files.

Multiple free alternatives to the expensive commercial font already exist, and developers have begun sharing resources mapping compatible replacements. The dramatic price increase may simply push studios toward these alternatives or open-source options like Google’s Noto font family.

Some major publishers develop custom fonts in-house to avoid external licensing dependency entirely. But smaller studios and indie developers typically rely on commercial providers, making sudden cost spikes particularly painful for teams operating on tight budgets.

When greed backfires

The pricing change appears designed for enterprise or internal software use where user counts stay below 25,000. Industry observers expect the new terms will drive customers away rather than generate the revenue increase the acquiring company likely projected.

Studios planning new projects can choose different fonts from the start to avoid these costs. Existing games may simply absorb the switching costs rather than continue to pay for the service, and the future of LETS seems uncertain.